CONDITIONS P - Z

These pages offer explanations of pediatric medical surgical conditions including:

- what the condition is

- signs and symptoms

- how it is diagnosed

- treatment

- home care

- long-term outcomes

Use it as a reference when discussing your child’s individual condition and treatment with your doctor and medical professionals.

Pancreas Divisum

Condition: Pancreas Divisum

Overview (“what is it?”)

- The pancreas is an organ that sits behind the stomach and secretes chemicals (called enzymes) that help in digestion.

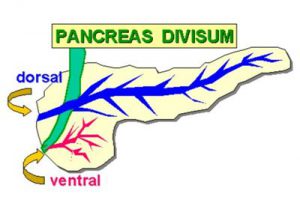

- Pancreas divisum is a congenital (meaning present at birth) pancreatic abnormality in which two parts of the pancreas fail to come together while the baby is developing inside the uterus (Figure 1). The digestive juice that the pancreas makes drain into the intestine through a tubular structure. Because of the failure of the pancreas to fuse, the duct does not drain the digestive juice effectively. The opening of the main pancreatic duct is narrowed.

Figure 1

Figure 1

- The number of people affected is unclear but it is believed to be present in as many as 5 to 10% of people.

- Pancreas divisum is sometimes associated with choledochal cysts or intestinal malrotation. These are congenital abnormalities of the gallbladder and intestines that occur during development.

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- The majority of individuals born with pancreas divisum experience no symptoms throughout life. These individuals will remain undiagnosed and do not require treatment. Approximately 5% of people will develop symptoms.

- Common symptoms include:

- Abdominal bloating and/or pain which is usually in the mid-abdomen (middle area of the upper belly) and sometimes radiates to the back

- Jaundice (or yellowing of the skin)

- Nausea

- Food intolerance

- Recurrent episodes of pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to find out what my child has?”)

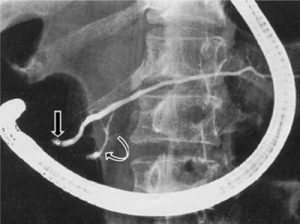

- The diagnosis of pancreas divisum is usually made by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography also known as an ERCP. ERCP is a special test where your child is sedated so that a flexible camera (called an EGD – esophagogastroduodenoscopy) can be inserted through the mouth down to the level of the pancreas to visualize the anatomy of the ducts (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has also been used successfully. It is an MRI scan specific for the pancreas

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)—uses a magnet, radio waves and computer to obtain images of organs in the body. MRI does not use radiation.

- This often requires some sedation for infants and young children

- Other tests that are occasionally done are abdominal ultrasounds, CT scans, amylase and lipase (blood tests for the pancreas function).

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child better?”)

- Endoscopic sphincteroplasty: The goal of endoscopic (flexible tube-like camera inserted into the intestines) therapy is to relieve the obstruction of the ducts that drain fluid from the pancreas to the intestines.This is done by enlarging or cutting the opening (sphincter) that will allow the pancreatic juice to drain into the intestines.

- Preoperative preparation depends on the condition of the child. If your child is dehydrated, has a bacterial blood infection (cholangitis), or currently suffering from inflammation of the pancreas, then these conditions need to be taken care of prior to the procedure (fluids, antibiotics, pancreatic rest)

- Postoperative care: Your child will recover in a monitored surgical ward, and the length of the hospital stay depends upon the child’s age, preprocedural condition and postprocedural complications.

- Risks: Immediate complications are injury to the esophagus, stomach or intestines, bleeding, infection and pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas).

- Benefits: Ability of pancreas to drain pancreatic juice effectively, relief of symptoms and recurrent pancreatitis

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: No dietary restrictions are necessary, and children are often allowed to resume their normal diet. If the child is recovering from pancreatitis, a low fat diet may be suggested.

- Activity: No activity restrictions apply. Your physician will give you specific instructions.

- Medicines: Mild pain relievers may be needed for the first days.

- What to call the doctor for

- Fevers, vomiting or food intolerance, or yellowing of the skin or eyes

- Worsening belly pain

- Follow-up care: Appointments may be frequent for the first month, and further endoscopic procedures may be necessary.Your physician will give you specific instructions for follow up.

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

Long-term results are dependent upon the procedure performed and associated abnormalities. Most patients have excellent long term results.

References

- Holcomb. G, and Murphy. P. Ashcraft’s Pediatric Surgery 5th Edition 2010, Elsevier.

- Madura JA, Fiore AC, O’Connor KW, et al. Pancreas divisum. Detection and management. American Surgery 1985; 51:353.

- O’Neill JA: Surgical management of recurrent pancreatitis in children with pancreas divisum. Annals of Surgery 231:899-908, 2000.

- http://pathology.jhu.edu/pc/BasicOverview1.php?area=ba.

- Figure-1-ERCP-showing-type-1classic-pancreatic-Divisum-with-major-dorsal-duct-opening.

Updated: 11/2016

Author: Romeo C. Ingacio, Jr., MD; L. Prescher, MD

Editors: Patricia Lange, MD; Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Pancreatic Cysts

Condition: Pancreatic Cysts (pseudocyst, fluid collections, duplication cyst)

Overview (“What is it?”)

- The pancreas is a gland located in the abdomen surrounded by the stomach, small intestine, liver, spleen and gallbladder (see Figure 1). The pancreas is a gland that aids in two bodily functions—digestion and blood sugar regulation.

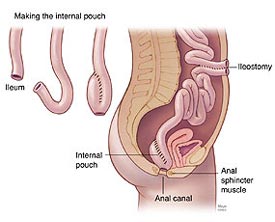

- Pancreatic cysts are collections of fluid that can be due to congenital (someone is born with it) or acquired (something that developed after birth) conditions. Pancreatic cysts are classified based on the underlying cause of the fluid collection.

- Pancreatic cysts are often classified into congenital and developmental, retention, enteric duplication and pseudocysts. The first three types of cysts are rare.

- Congenital and developmental cysts may be detected on prenatal ultrasound. These cysts may be associated with cysts in other areas of the body.

- Retention cysts are a result of blockage of a portion of the gland downstream causing a back-up of fluid.

- Duplications of the gastrointestinal (enteric) system may involve the pancreas and lead to cyst formation. Duplication cysts are abnormal portions of the intestine. In this location, there may be duplication of the pancreas or duplication of an organ next to the pancreas.

- The most common cause of a pancreatic fluid collection is a pseudocyst. This type of fluid collection is a result of inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) or trauma to the pancreas. The fluid leaks from the injured pancreatic ducts and collects in areas next to the pancreas. Over time, a capsule forms around this fluid collection becoming a pseudocyst.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- Congenital/developmental cysts or enteric duplications may be seen on prenatal ultrasound. Early signs of cysts may be feeling of fullness or bloating and early satiety or decreased appetite. A history of pancreatitis or pancreatic trauma may be an early indication that a pseudocyst may form.

- Later signs/symptoms include pain and discomfort due to the cyst. A mass may be detected on physical exam if the cyst becomes large. Patients may also develop jaundice, persistent vomiting, weight loss and fluid within the abdomen.

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to find out what my child has?”)

- Labs and tests: The most common lab tests include a serum amylase and lipase as well as liver function tests (bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, GGT, AST, ALT). In many cases, all or most of these labs will be normal.

- Diagnosis is usually first made with ultrasound.

- Once the diagnosis is made with ultrasound, additional imaging with CT scan or MRI maybe obtained to provide more detailed anatomic information about the cyst.

- Conditions that mimic this condition include other cystic lesions in nearby organs (adrenal gland, duodenum, stomach, etc.).

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child better?”)

- There are really no medications that can be used to treat pancreatic cysts. Some pancreatic fluid collections that develop after trauma or pancreatitis may resolve over time. Medications may be required to treat complications associated with pancreatic cysts (i.e. antibiotics if the cyst becomes infected).

- Surgery is the main treatment for pancreatic cysts.

- Preoperative preparation: Patients will usually have preoperative labs and imaging (see above). Patients will often require blood to be available during surgery. Children will not be able to eat the morning of surgery.

- Postoperative care: Most patients will not be allowed to eat or drink immediately after surgery. This will allow for everything to heal on the inside. Many patients will have a tube in place to keep the stomach empty. This tube is usually inserted through the nose and into the stomach while the patient is asleep under anesthesia. Some patients may have a drain in place after surgery. Most of the time, the drain is removed prior to going home. However, in some instances the drain may be left in place to collect additional fluid. If this is the case, parents will be given careful instruction on how to care for the drain. In most instances, when children are discharged from the hospital, they are eating normally and require minimal additional care.

- Risks/Benefits: The standard risks of surgery include bleeding, blood transfusion, infection, anesthetic risks, damage to surrounding structures, leakage from the pancreas and recurrent fluid collections. The benefit of surgery is to relieve symptoms and to prevent future complications associated with the pancreatic cysts (infection, bleeding, etc.).

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: In most cases, a regular diet

- Activity: No heavy activity for 4-6 weeks for an open operation and 2-4 weeks for a laparoscopic operation

- Wound care: None, unless a drain is still in place

- Medicines: Pain medicine for a couple of days

- What to call the doctor for: Fever greater than 101⁰ F or 38⁰C, persistent vomiting, wound problems (redness or drainage), or worsening pain.

- Follow-up care: With your surgeon 1-2 weeks after discharge.

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

In most cases, surgical excision or drainage of the cyst will be curative.

Updated: 11/2016

Author: Steven L. Lee, MD

Editors: Patricia Lange, MD; Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Pancreatitis

Condition: Pancreatitis in children

Overview (“What is it?”)

- The pancreas is a gland located in the abdomen surrounded by the stomach, small intestine, liver, spleen and gallbladder. The pancreas is a gland that aids in two bodily functions—digestion and blood sugar regulation. The pancreatic duct is a tube that runs the length of the pancreas and carries pancreatic enzymes and other secretions made by the pancreas, often called “pancreatic juice”. This pancreatic duct connects with the common bile duct, which carries bile from the gallbladder. These two ducts drain bile and pancreatic juice to into the small intestine, where these substances aid with the breakdown of food. The hormones that regulate blood sugar (insulin and glucagon) are released into the blood stream rather than the intestine.

- Definition: Pancreatitis is a disease in which the pancreas becomes inflamed from a number of different causes. Pancreatic damage occurs when enzymes in the pancreatic juice are activated before they are released into the small intestine and begin attacking the pancreas. Acute pancreatitis is a sudden inflammation that ranges from mild to severe. It can be life threatening.

- Most children with acute pancreatitis recover completely with appropriate treatment. In severe cases, acute pancreatitis can result in bleeding into the gland, infection and cyst formation. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis may also suffer problems in other organs such at the kidneys, lungs and heart. Common causes of acute pancreatitis in children include injury (such as handlebar injuries from a bicycle), gallstones which lodge in the opening of the pancreatic duct, certain medications (some anti-seizure medications, or drugs used to treat cancer) or congenital problems of how ducts of the pancreas formed during fetal development.

- Chronic pancreatitis is a slow, progressive illness of the pancreas in which the ability of the pancreas to produce pancreatic juices and the sugar controlling hormones becomes altered. Children at risk for chronic pancreatitis are those with specific genetic, metabolic or anatomic abnormalities.

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

Common symptoms of pancreatitis include abdominal and back pain, nausea and vomiting. These symptoms are not limited to pancreatitis and can easily be confused with signs of another disease. Patients with chronic pancreatitis may experience weight loss, diarrhea and oily bowel movements, poor growth and diabetes.

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to find out what my child has?”)

- There is no single test to diagnose pancreatitis. The rapid onset of upper mid-abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting may prompt your doctor to obtain blood tests to see if there is evidence of pancreatitis. Testing the blood for substances that the pancreas makes (amylase and lipase) is used most commonly. When the pancreas is injured or inflamed, the blood levels of these pancreatic enzymes can rise above normal. If these blood tests are abnormal, an ultrasound or CT scans are commonly obtained to look for evidence of pancreatitis. However, all of these tests may be falsely normal in the setting of pancreatitis, and repeated vigilance on the behalf of the medical team may be required to ultimately make the diagnosis.

- Blood tests may be used to determine if the pancreatitis is improving, and imaging such as another CT scan or an MRI may be used if there is suspicion of ongoing damage to the pancreas, development of a cyst (called a pseudocyst), or to try and determine if abnormal anatomy of the pancreatic duct system is the cause of the pancreatitis.

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child better?”)

- Acute pancreatitis typically resolves within 2-7 days with appropriate intravenous fluid, pain control and nutritional support. In the past, patients were prevented from eating to allow the pancreas to rest (“bowel rest”), but today your doctor will decide what is safe—either limited oral intake, using nutrition delivered through a special tube placed through the nose (a nasojejunal tube), or nutrition given through the vein in severe cases. In cases of severe vomiting, the stomach may need to be suctioned to empty it out. This is done through a tube inserted through the nose with the end in the stomach. If the stomach is empty, then the vomiting usually stops, making the child more comfortable. Supporting other organ systems is important and may require admission to the intensive care unit so that the lungs, kidneys and heart can be supported with modern medical interventions when necessary.

- A surgeon may be involved in caring for your child as there is always a small chance that an operation or procedure may be necessary, but this is uncommon to treat the pancreas itself. However, in some cases, surgery may be necessary to treat the cause of the pancreatitis. For instance, when pancreatitis occurs as the result of gallstones, removal of the gallbladder is often recommended once the pancreatitis has resolved. This is typically done with an operation called a laparoscopic cholecystectomy in which the gallbladder is removed using small incisions. In patients with pancreatitis from trauma, a pediatric surgeon will likely care for your child to determine if surgery is necessary to remove a part of the damaged pancreas. Also, a surgeon may be helpful in cases where complications happen as the result of severe pancreatitis such as a pancreatic cyst or bleeding.

- The treatment of chronic pancreatitis largely depends on the cause. If there is problem with the anatomy of the duct system that drains the pancreas, then a procedure may be needed. This is often performed by endoscopy whereby a scope is inserted into the mouth that reaches the pancreatic duct opening in the intestine (endoscopy) under anesthesia. Surgery may be required if this is unsuccessful or is unavailable.

- Patients who have lost the ability to digest food will be prescribed pills containing pancreatic enzymes and special vitamins to aid in digestion. There is no clear evidence that a special diet is required for chronic pancreatitis, however many doctors will advise low-fat diet and more frequent, smaller meals. Currently, there are no effective medical treatments for patients with a genetic predisposition, however some patients are candidates for a newer operation called pancreatectomy with islet cell autotransplantion that is offered in some specialized medical centers. In this procedure, the surgeon removes the pancreas and the hormone-producing cells known as ‘islets’ are isolated and returned to the patient, usually by injecting them into the liver.

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

- When the symptoms are mild and the patient is able to drink enough liquids and be comfortable with oral pain medication, your child may not need to be treated in the hospital. When your child is hospitalized, even though symptoms of acute pancreatitis may last for a few days, it does not mean that your child needs to stay in the hospital that entire time.

- The complications of acute pancreatitis depend on how bad the inflammation was. The most common complication is the collection of fluid around the pancreas, which, in many cases, will resolve with time. If the pockets of fluid become infected or get really big, then a procedure may be necessary. This may include drainage of infected fluid or surgery.

- Death from acute pancreatitis is quite rare in children. Pancreatitis can recur in 10% of patients and patients who have recurrent episodes will likely benefit from further testing to determine the underlying cause.

Updated: 11/2016

Author: Casey M. Calkins, MD

Editors: Patricia Lange, MD; Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Parathyroid Problems

Condition: Parathyroid problems in children

Overview (“What is it?”)

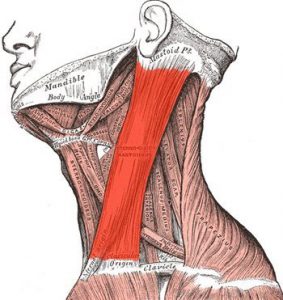

- Parathyroid glands are small organs of the endocrine system that are located in the neck behind the thyroid. Parathyroid glands (we all generally have four of them) are normally the size of a pea (or even smaller). These glands control the calcium in our bodies by making a hormone called parathyroid hormone or “PTH”. PTH controls the level of calcium and phosphorus—minerals that are bones but also circulates in the blood. PTH controls how much calcium is lost in the urine (by its effects on the kidneys) and works with vitamin D to control how much calcium we absorb from our food.

- Our bodies very carefully regulate calcium because it is important in many of the body’s functions. If the parathyroid glands make too much or too little hormone, it disrupts this delicate balance. If the glands do not make enough PTH, then you have hypoparathyroidism. More commonly, diseases of the parathyroid gland result in hyperparathyroidism—where your body is making too much PTH and the blood calcium rises. Too much calcium in the blood is called hypercalcemia. Although the thyroid and parathyroid glands are neighbors and are part of the endocrine system, the thyroid and parathyroid glands are not unrelated—they just have similar names. Parathyroid problems in children are less common in children compared to adults.

- Definition

- Hypoparathyroidism: Not enough PTH and low blood calcium levels is most commonly caused by injury during an operation of the parathyroid glands—but it only happens in 1-2% of those patients. Some children are born without parathyroid glands, or glands that cannot make enough PTH such as DiGeorge syndrome. Although DiGeorge syndrome may affect one baby out of every 2,000 births, not all of those children will suffer from hypoparathyroidism.

- Hyperparathyroidism: Too much PTH and high body calcium can be caused by a number of problems, but there are two general types.

- In primary hyperparathyroidism, an enlargement of one or more of the parathyroid glands causes too much PTH to be made and therefore high calcium in the blood. The chance of primary hyperparathyroidism in a child is less than 5 in 100,000. The most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism is a benign (non-cancerous growth) tumor on a single parathyroid gland that makes it overactive. Sometimes, extra hormone is made from all four parathyroid glands being bigger than normal. Cancer of the parathyroid glands is very uncommon, but usually causes symptoms that are also due to high blood calcium levels.

- Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs as a result of another disease that initially causes low levels of calcium in the body which this causes the parathyroid glands to make lots of PTH in an effort to increase blood calcium levels. Over time, this may cause hypercalcemia. Chronic kidney failure is the most common cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism as the kidneys have lost the ability to retain enough calcium in the body.

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- Hypoparathyroidism: In mild cases, there may be no symptoms at all. When symptoms are seen, they are usually vague. Health care professionals call these symptoms “nonspecific”. These include feeling tired, irritable, depressed or anxious. When calcium levels drop very low, the patient may experience muscle or abdominal pain, tingling of the fingers, toes or face, numbness around the mouth, twitching of the face muscles, headaches, brittle nails, dry skin and hair, and uncontrolled spasms that cause muscle cramps. When calcium levels fall very fast or are extremely low, patients may experience seizures.

- Hyperparathyroidism: Like hypoparathyroidism, mild cases of hyperparathyroidism may cause no symptoms. When symptoms are seen, they are also vague and many are very similar to having low calcium levels. In mild cases these include muscle weakness, feeling tired, weak or depressed or muscle pain. In severe cases the patient may experience back or flank pain from kidney stones, belly pain, troubles concentrating, personality changes, memory problems, constipation or broken bones.

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to find out what my child has?”)

- Doctors usually diagnose a parathyroid problem after finding an abnormal level of calcium on a blood test when a child has some of the symptoms noted previously. It is especially important to tell the doctor about other family members that may have had similar calcium or parathyroid problems in the past. If the child was healthy before the onset of symptoms, then high calcium is almost always due to primary hyperparathyroidism. To narrow down why there is too much calcium in the blood, your doctor may also obtain other blood tests to look at the level of other elements in your body such as phosphorous, alkaline phosphate and the PTH level.

- The doctor may also order a test of the urine to see if the high blood calcium levels are due to a kidney problem.

- A special X-ray called “bone densitometry” is more commonly done in adults to see if the parathyroid problem has caused damage to the bones. This test is not performed commonly in children because a child’s bones are still growing and adapting, and the results of that X-ray test are unreliable in kids.

- The most common reason why the parathyroid gland works too hard is overgrowth of a single parathyroid gland called an “adenoma”. An adenoma is a benign (non-cancerous) growth that only causes a problem because it makes too much parathyroid hormone. Less commonly, one or more glands just get too large, which is called parathyroid hyperplasia. To see if there is evidence of an adenoma, the doctor may order a Sestamibi scan. Sestamibi is a very safe liquid radioactive compound that is absorbed by the overactive parathyroid but not by the healthy ones. The compound is injected through a small IV and then a special X-ray machine called a gamma camera is used to try and identify the abnormal parathyroid gland(s). This test is performed to locate which gland or glands may be abnormal to plan for treatment.

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child better?”)

- Patients with low blood calcium (hypoparathyroidism) are treated with medicine to replace calcium to keep the blood levels normal. These medicines include calcium and vitamin D (Calcitrol®), both of which can be given by mouth to maintain a normal level of calcium circulating in the body. Currently, giving a patient a drug that mimics PTH is not practical or effective. There is no surgical treatment for hypocalcemia.

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Medical Management: Although researchers continue to try and find medicines for the treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism, there are no medicines are currently available that can block the overproduction or PTH. In patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism that occurs with chronic kidney problems, medicine is available to try and treat the problem, and surgery is typically used as a last resort. For the rare patient who has severe hypercalcemia that has resulted in a seizure or other life-threatening problems, immediate admission to the hospital for intensive therapy with IV fluids and other medicines to bring the calcium level down to a lower level is required prior to considering any type of surgery.

- Surgical Treatment: The standard and most effective treatment for primary hyperparathyroidism is to remove the parathyroid tissue that is overproducing PTH—typically a single adenoma. The Sestamibi scan helps the surgeon to determine which gland(s) is abnormal and allows him or her to focus the operation on removal of the overactive gland(s). This operation is done under general anesthesia though a small incision (1-2 inches) in the neck. The surgeon identifies the abnormal gland and removes it. Many surgeons confirm that the gland in question is the only problem gland prior to closing the incision by using a blood test, while the patient is still under anesthesia, to make sure the PTH level has dropped to a more normal level after the gland has been removed. Since PTH doesn’t last for very long in the body, once the surgeon takes the gland out, the PTH level should drop to a normal level within 20-30 minutes.

- Risks from parathyroid surgery include temporary low blood calcium levels while the other normal parathyroid glands left behind regain their ability to make PTH. In modern surgery where the surgeon removes the adenoma and doesn’t “explore” the other glands, this may last a few days, and is generally treated with oral calcium supplements until it gets better. Risk of damage to a nerve that is close to the parathyroid glands (recurrent laryngeal nerve) is low (1%). If the nerve is injured, it typically regains function, but if the nerve is permanently damaged it can cause permanent hoarseness. This is very rare in the hands of a surgeon with considerable experience in parathyroid surgery.

- Benefits: Removing the overactive gland resolves the symptoms of high calcium. Bones are stronger.The results of surgery are generally excellent, with more than 99% of patients being “cured” of the disease, and in the vast majority of cases there is little risk of the high calcium levels returning because of disease of another parathyroid.

- Postoperative care: The operation may require an overnight stay just to ensure that the patient doesn’t exhibit any symptoms that would require more aggressive therapy for the temporary low calcium levels.

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: Usually the child can be on a regular diet appropriate for age when he or she goes home.

- Activity: Regular activity can resume slowly a few days after surgery.

- Wound care: Specific wound care issues should be addressed with your child’s surgeon. Usually wounds are kept dry for about three days, then the child may shower. Soaking the wound (such as baths or swimming) should wait until a week after surgery.

- Medicines

- Medicines for pain such as acetaminophen (Tylenol®) or ibuprofen (Motrin® or Advil®) or something stronger like a narcotic may be needed to help with pain for a few days after surgery. Stool softeners and laxatives are needed to help regular stooling after surgery, especially if narcotics are still needed for pain.

- If your child has persistent low calcium levels, he or she will need calcium supplements.

- What to call the doctor for: Call to the surgeon if there is worry about infection (unexplained fevers, redness and drainage of the wound). If your child experiences numbness and/or tingling around the fingers and the face, you should call the surgeon or endocrinologist as well.

- Follow-up care: A wound check is often performed 2-3 weeks after surgery. Often, the child’s oncologist can also provide follow up of the wound as well.

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

Future outcomes for hypercalcemia secondary to hyperparathyroidism is excellent.

Updated: 11/2016

Author and Editor: Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Condition: Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA)

Overview (“What is it?”)

- Definition: The ductus arteriosus is a connection between the aorta (large blood vessel that carries blood to the entire body) and the pulmonary artery (blood vessel that carries blood to the lungs). This is a structure that is very important while the baby is developing inside the mother, because through it, the mother provides oxygen to the baby. When the baby is born, the baby starts breathing and the ductus arteriosus is not needed anymore. Normally it closes on its own after birth. Sometimes, especially in premature babies, the ductus stays open (“patent”)—thus, the condition is named “patent ductus arteriosus” (PDA). Blood that is supposed to go to the body will instead go to the lungs. This situation can cause too much blood to go to the lungs, requiring the baby to remain on the ventilator for a long time.

- Epidemiology: Happens in 7-38% premature babies

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- Early signs

- Murmur heard on exam

- Needs oxygen

- Blood pressure changes

- Later signs/symptoms

- Congestive heart failure—heart needs to work harder and over time, it may not be able to keep up

- Need to be on the ventilator a long time

- Murmur heard on exam in older kids

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to find out what my child has?”)

- Labs and tests

- Exam: Murmur heard with stethoscope

- Chest X-ray: Findings of an enlarged heart or fluid in the lungs

- Echo (ultrasound of the heart) shows the presence and size of the PDA and the flow of blood in PDA

- Conditions that mimic this condition

- Lung disease due to prematurity (bronchopulmonary dysplasia)

- These babies will also have lung problems requiring ventilator but no murmur or PDA seen on echo.

- Lung disease due to prematurity (bronchopulmonary dysplasia)

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child better?”)

- Medicine

- There are medicines that can be given to help close the ductus. Indomethacin and acetaminophen are two of these medications.

- Risk of indomethacin includes association with intestinal perforation, bleeding and kidney abnormality.

- There are medicines that can be given to help close the ductus. Indomethacin and acetaminophen are two of these medications.

- Surgery

- Surgery is the only option if the baby fails medical therapy or if complications happen because of the medicines given to close the ductus.

- Procedure

- Can be done in the operating room or in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)

- Left thoracotomy (incision on side of left chest between ribs)

- Place clip on PDA to close it

- Older children can have PDA closed by placement of coils in PDA by accessing it using catheters through the artery in the groin (transcatheter coil embolization).

- Preoperative preparation: Antibiotics are given by vein to decrease risk of infection.

- Postoperative care

- Chest X-ray after surgery

- Supportive care (fluids, possible blood pressure medication, ventilator, pain medication) after surgery. It will take some time for the baby to recover from surgery and get used to new blood circulation.

- A small tube may be placed in the chest cavity after the surgery to drain extra air and fluid. This will be removed a few days after the operation.

- Risks

- Bleeding

- Damage to lung (low)

- Damage to nerve (recurrent laryngeal nerve) which can affect vocal cord on left side. Voice is preserved, but may have swallowing problems.

- Death (low incidence but can happen due to bleeding)

- Benefits

- Improve baby’s lungs and may help baby to get off the ventilator

- Improve blood flow to intestines and rest of body

- Improve heart function

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: Formula or breast milk appropriate for the baby

- Activity: By the time baby goes home, activity should be normal

- Wound care: Incision on chest can be washed with soap and water.

- Medicines: Nothing particular to this condition

- What to call the doctor for: Redness, warmth, drainage from incision, fever, problems breathing

- Follow-up care: The surgeon usually sees baby two weeks after surgery (if baby is still in hospital, the surgeon will usually see baby while still in hospital)

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

No significant long-term outcomes except that the titanium clip (if used) will always be visible on chest X-ray (but will not go off in metal detectors or have problems with MRIs).

Updated: 11/2016

Author: Grace Mak, MD

Editors: Patricia Lange, MD; Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Pectus Carinatum

Condition: Pectus Carinatum (pigeon chest)

Overview (“What is it?”)

- Pectus carinatum is a condition where the bones of the chest did not develop as they should. The chest cage is made up of the center breast bone (sternum) in the front, the ribs (made of bone and cartilage, with the cartilage connecting the ribs to the breast bone), and the spine in the back. In pectus carinatum, the breast bone is pushed out. One side of the chest may be more affected giving an uneven look

- Epidemiology: More common in males than females. It can get worse with age, especially during growth spurts.

- Etiology (cause): Some people think that the cartilaginous ribs grow unevenly, pushing the breastbone outward. Sometimes it can be seen members of the same family. Pectus carinatum can also be seen in children who had cardiac surgery as babies, with incisions in the breast bone.

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- Pectus carinatum abnormalities range from barely noticeable to severe.

- Early symptoms: The outward appearance of the chest is something that the child and parents can see.

- Late symptoms: On occasion, there may be trouble breathing or irregular heart rate, but these are rare. Sometimes there may be pain the area of the chest.

- Associated problems: Children with pectus carinatum may have scoliosis (abnormal curve of the spine). Some may also have connective tissue problems.

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to see what my child has?”)

- Chest X-ray: May initially be done to look at the general appearance of the breast bone, ribs and spine.

- Computed tomography (CT) of chest: Detailed pictures of the chest are taken, reconstructed in different views to get a better picture of the chest. This shows the doctor how bad the pectus is—mild, moderate or severe.

- Echocardiography: Ultrasound of the heart to look at flows and function. This is not done routinely, but may be ordered if there is concern about heart function.

- Lung function tests: Testing how strong the lungs are. Again, not all patients need this; your doctor will decide whether your child requires this study.

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child get better?)

- Medical management—BRACING: There is no medicine that can make pectus carinatum better. However, if the pectus carinatum is mild to moderate, the use of a custom-fitted chest wall brace has good results.

- The brace is constructed to fit your child’s chest.

- As the child grows, the contour of the chest changes. The brace will need to be changed.

- THE BRACE WILL ONLY WORK IF THE CHILD WEARS IT. The child should wear it as much as possible (greater than 20 hours a day, if possible).

- Every six months, there is follow up with your surgeon

- Surgery: For severe pectus carinatum with symptoms, surgery may be considered. Surgery is usually delayed until middle teenager years.

- Ravitch Procedure: The goal of the surgery is to straighten out the breast bone. The cartilaginous ribs are removed from their connection to the breast bone. The breast bone may have to be fractured before it can be straightened out, and a strut may be placed as the breast bone heals. Drains are placed under the muscle and skin to collect fluid.

- Preoperative preparation: The child is asked to shower or bathe the night before or the morning of surgery. He or she should not eat anything solid for at least eight hours before surgery.

- Postoperative care: The child is admitted to the hospital for several days. Pain control is achieved using epidural anesthesia, patient controlled analgesia (PCA), nerve cryoablation, oral pain medications.

- Pain medications can be given by mouth or through the vein. These may include acetaminophen (Tylenol®), ketorolac or ibuprofen, as well as narcotics.

- PCA: Patient controls when pain medication is given. A syringe of pain medication is connected to the patient’s IV. Based on the patient’s weight, a safe dose of narcotic is given each time patient pushes a button.

- Epidural: A long thin catheter is placed in the spine around the spinal cord. Pain medications are injected through this route, which the patient may also be able to control with a button.

- Gradual activity is directed by the surgical, nursing, and physical therapy teams.

- In a Ravitch procedure, drains to collect fluid after surgery will be removed before discharge

- Ravitch Procedure: The goal of the surgery is to straighten out the breast bone. The cartilaginous ribs are removed from their connection to the breast bone. The breast bone may have to be fractured before it can be straightened out, and a strut may be placed as the breast bone heals. Drains are placed under the muscle and skin to collect fluid.

- Risks: Bleeding, infection, pain

- Benefits: The chest wall is straightened out.

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: Most patients are able to eat a general diet.

- Activity: Ask your surgeon for specific recommendations. It is generally recommended to limit activity, especially those that twist the body or use the arm significantly (golf, tennis, swimming), for at least six months after surgery. Vigorous activity may dislodge the bar, and the patient would need another operation.

- Wound care: The patient can shower in three days but may want to wait seven days after surgery before soaking the wound. If drains are still present, do not wet the drains.

- Medicines: Medication for pain such as acetaminophen (Tylenol®) or ibuprofen (Motrin® or Advil®) or something stronger like a narcotic may be needed to help with pain for a few days after surgery. Stool softeners and laxatives are needed to help regular stooling after surgery, especially if narcotics are still needed for pain. Constipation is a very common problem after this surgery.

- What to call the doctor for: Problems that may indicate infection such as fevers, wound redness and drainage should be addressed. If the patient feels at any time that the strut has moved or there is chest pain, call the doctor.

- Follow-up care: The patient should be seen by the surgeon a few weeks after surgery to check on the wound, the shape of the chest, and/or placement of the strut. These strut is removed a few months after surgery..

Long-Term Outcomes

The normal shape of the chest is maintained in majority of children after the Ravitch operation.

Updated: 11/2016

Author and editor: Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Pectus Excavatum

Condition: Pectus Excavatum (sunken chest, funnel chest)

Overview (“What is it?”)

- Pectus excavatum is a condition where the bones of the chest did not develop as they should. The chest cage is made up of the center breast bone (sternum) in the front, the ribs (made of bone and cartilage, with the cartilage connecting the ribs to the breast bone), and the spine in the back. In pectus excavatum, the breast bone appears sunken or hollowed out. Sometimes the ribs are also malformed and do not appear even.

- Pectus excavatum means hollowed chest.

- Epidemiology: It occurs in 1 in 400 births.

- Etiology (cause): Sometimes the child may have been born with a pectus. It may get worse with age. Some people think that the cartilaginous ribs grow unevenly, pushing down the breastbone. Some patients with problems of bones and cartilage (Marfan’s syndrome) can have a higher risk of pectus excavatum.

Figure 1: Pectus excavatum. Picture courtesy of MJArca 12/2016

Figure 1: Pectus excavatum. Picture courtesy of MJArca 12/2016

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- Early symptoms: A hollow appearance of the breast bone, asymmetry of the ribs and the lower edges of the ribs.

- Late symptoms: Worsening deformity. Occasionally may have problems breathing during exertion. Occasionally, pectus may cause breathing troubles or heart issues.

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to see what my child has?”)

- Computed tomography (CT) of chest: Detailed pictures of the chest are taken, reconstructed in different views to get a better picture of the chest. This shows the doctor how bad the pectus is—mild, moderate, or severe.

- Echocardiography: Ultrasound of the heart to look at flows and function. This is not done routinely, but may be ordered if there is concern about heart function.

- Lung function tests: Testing how strong the lungs are. Again, not all patients need this; your doctor will decide whether your child requires this study.

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child get better?)

- Medical management: There is no medicine that can make pectus excavatum better. However, if the pectus excavatum is mild, exercises can make the chest muscles stronger. Being more conscious of having a good posture is also very helpful.

- Surgery: For moderate or severe pectus with symptoms, surgery may be considered. Surgery is usually delayed until middle teenager years. This can be done using two approaches.

-

Nuss Procedure: A steel bar is used to push out the breast bone. The bar stays in the chest for two to three years.

Nuss Procedure: A steel bar is used to push out the breast bone. The bar stays in the chest for two to three years. - Ravitch Procedure: The cartilaginous ribs are removed from their connection to the breast bone. The breast bone may have to be fractured before it can be straightened out, and a strut may be placed as the breast bone heals.

- Preoperative preparation: The child is asked to shower or bathe the night before or the morning of surgery. He or she should not eat anything solid for at least eight hours before surgery.

- Postoperative care: The child is admitted to the hospital for several days. Pain control is achieved using epidural anesthesia, patient controlled analgesia (PCA), nerve cryoablation, oral pain medications

- Epidural: A long thin catheter is placed in the spine around the spinal cord. Pain medications are injected through this route, which the patient may also be able to control with a button.

- PCA: Patient controls when pain medication is given. A syringe of pain medication is connected to the patient’s IV. Based on the patient’s weight, a safe dose of narcotic is given each time patient pushes a button.

- Nerve cryoablation: This method is available in certain centers where the nerves by the ribs are frozen. There is numbness in the area around where the incisions and the bar are located. This method is currently only available for the Nuss procedure.

- Pain medications can be given by mouth or through the vein. These may include acetaminophen (Tylenol®), ketorolac or ibuprofen, as well as narcotics.

- Gradual activity is directed by the surgical, nursing and physical therapy teams.

- In a Ravitch procedure, drains to collect fluid after surgery will be removed before discharge.

- Risks: Bleeding, infection, pain. If the patient has Nuss procedure, the bar can get dislodged.

- Benefits: The chest wall is straightened out.

-

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: Most patients are able to eat a general diet.

- Activity: Ask your surgeon for specific recommendations. It is generally recommended to limit activity, especially those that twist the body or use the arm significantly (golf, tennis, swimming), for at least six months after surgery. Vigorous activity may dislodge the bar, and the patient would need another operation.

- Wound care: The patient can shower in three days but may want to wait 5-7 days after surgery before soaking the wound.

- Medicines: Medication for pain such as acetaminophen (Tylenol®) or ibuprofen (Motrin® or Advil®) or something stronger like a narcotic may be needed to help with pain for a few days after surgery. Stool softeners and laxatives are needed to help regular stooling after surgery, especially if narcotics are still needed for pain. Constipation is a very common problem after this surgery.

- What to call the doctor for: Problems that may indicate infection such as fevers, wound redness and drainage should be addressed. If the patient feels at any time that the bar has moved or there is chest pain, call the doctor.

- Follow-up care: The patient should be seen by the surgeon a few weeks after surgery to check on the wound, the shape of the chest, and/or placement of the bar. These visits will continue until the bar is removed in 2-3 years. If a Ravitch procedure is done, the strut may be removed sooner.

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

The normal shape of the chest is maintained in majority of children after the Ravitch or Nuss procedure.

Updated: 11/2016

Author and editor: Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Rectal Prolapse

Condition: Rectal Prolapse

Overview (“What is it?”)

The rectum is the end of the large intestine (also known as the colon) where stool travels before it exits outside through the anus.

- Rectal prolapse is condition where a portion or all of the rectum (the end of the colon) protrudes through the anus and can be seen on the outside of the body. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2: Infant with rectal prolapse. (Pictures provided by Dr. Romeo C. Ignacio, Naval Medical Center San Diego, California)

Figure 2: Infant with rectal prolapse. (Pictures provided by Dr. Romeo C. Ignacio, Naval Medical Center San Diego, California)

- Rectal prolapse affects boys and girls equally, but is rarely seen in the absence of predisposing conditions. It is most commonly seen from infancy to four years of age (potty training phase).

- Predisposing conditions include the following conditions:

- Cystic fibrosis which is a genetic (inherited) disease that can lead to chronic respiratory problems and gastrointestinal symptoms

- Diarrheal diseases

- Malnutrition

- Weakness of the muscles of the pelvis

- Conditions that increase pressure in the abdomen which include chronic cough, constipation, toilet training and excessive vomiting. Chronic constipation and excessive straining is the cause in approximately 15% of causes.

- Prolapse may range from minor, which goes away spontaneously, to more severe cases that require the tissue be pushed back in manually.

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- Rectal prolapse is usually obvious based on physical exam alone. It appears as a dark red mass at the anus. The mass may only be present during stooling. (See Figure 3A)

- A mass at the anus that does not go away on its own needs immediate medical attention. This mass needs to be pushed back in before the blood to the segment is compromised.

- Rectal prolapse is associated with discomfort of having something coming out of the bottom. Increasing pain might mean that the tissue coming out may not be getting good blood flow.

- Sometimes there can be passage of mucous or small amounts of blood.

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to find out what my child has?”)

- Usually no blood tests are needed for the diagnosis of prolapse. If other clinical signs are present to worry about cystic fibrosis, malnutrition or weakness, then blood tests may be sent to see if these conditions are present.

- Depending on the age of the child and the clinical situation, an X-ray of the belly may be needed. Additionally, a contrast enema may also be helpful. In this test, a tube is placed inside the child’s anus and contrast liquid is injected slowly. The contrast lights up the inside of the rectum and large intestine. This study shows the anatomy of the large intestine to see if anything may contribute to rectal prolapse.

- Rectal prolapse may be transient. Your health care provider may ask your child to sit on the commode in the office to see if the prolapse would happen. Additionally, pictures taken at home can be helpful because the prolapse may not happen during the clinic visit.

Prevention

- AVOIDING rectal prolapse is the main way of dealing with the problem.

- If a child has constipation resulting in straining and sitting on the toilet for a long time, the sphincter muscle that holds the rectum in relaxes and makes prolapse happen. Recommended changes in defecation habits. Avoiding constipating foods such as milk products, rice and bananas may help. Medications such as polyethylene glycol (Miralax®), docusate and senna may be helpful in keeping stools soft.

- Changes in stooling habits may include: restriction of time spent on the commode, use of a child-specific commode or placement of a stepstool in front of an adult commode. Having the child sit on the toilet for a long time during potty training can contribute to prolapse; limiting time on the toilet is important.

- A chronic cough should be treated.

- If diarrhea is present, it should be treated.

- Specific medical treatments may be necessary in some cases, such as cystic fibrosis (which requires enzyme replacement) to prevent recurrent prolapse.

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child better?”)

- In the majority of cases, rectal prolapse reduces on its own mostly after the child stops squatting.

- If the rectal prolapse does not go back on its own, gently pushing back (reduction) of any tissue with some lubricant may help. Having the child lay on the side and relax may aid in this.

- If not successful, apply granulated sugar to the prolapsed rectum. Let the sugar sit for 15 minutes and then attempt to reduce the prolapse again. The sugar will absorb the extra water in the prolapse and cause the prolapse to shrink. You must use granulated sugar. A sugar substitute will not work for reducing the prolapse.

- If not successful, bring child to doctor.

- At times, your health care provider may gently reduce the prolapse using gloves and lubricant. If prolapse recurs shortly after reduction, taping your child’s buttocks together temporarily may have decrease the swelling in the tissue.

- Surgery may be necessary in cases where medical therapy and changes in defecation habits are not successful. Operative therapy may also be required to reduce a prolapsed rectum that cannot be reduced manually, ulcerations (injury to the lining of the rectum), painful prolapse or excessive bleeding.

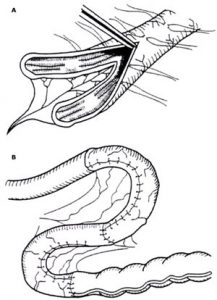

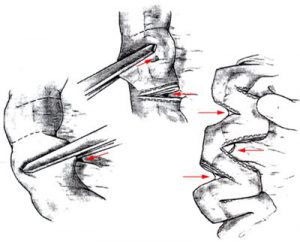

- A number of surgical procedures are used (See Figure 3B – 3D). The choice of procedure is determined based on the severity of the prolapse, the underlying cause or condition, the severity of symptoms and the experience of the treating surgeon. The surgeon will check whether the rectum is healthy.

Figures 3A – 3D. Infant with rectal prolapse (2A upper left corner). Figure 3B (lower left corner) shows an infant with recurrent rectal prolapse who underwent a modified Thiersch procedure. Figure 3C (upper right corner) shows the suture tightened over a metal rectal dilator. Figure 3D (lower right corner) shows postoperative result with resolution of rectal prolapse. (Pictures provided by Dr. Romeo C. Ignacio, Naval Medical Center San Diego, California)

Figures 3A – 3D. Infant with rectal prolapse (2A upper left corner). Figure 3B (lower left corner) shows an infant with recurrent rectal prolapse who underwent a modified Thiersch procedure. Figure 3C (upper right corner) shows the suture tightened over a metal rectal dilator. Figure 3D (lower right corner) shows postoperative result with resolution of rectal prolapse. (Pictures provided by Dr. Romeo C. Ignacio, Naval Medical Center San Diego, California)

- In certain patients with a redundant rectosigmoid colon, consideration will be given to removal of this segment and fixing the remaining segment internally (rectopexy). This procedure is done either open (large incision on the belly) or laparoscopically (multiple small incisions on the belly to allow a video camera and small instruments to perform the procedure).

- Preoperative preparation: If the child is taken to the operating room to reduce prolapse as an emergency, antibiotics will be given to decrease infection. For scheduled cases where part of the large intestine may be removed, the child may need to drink fluid to clear stool out of the intestines.

- Postoperative care:

- Activity: Typically, the child is encouraged to walk around as soon as possible.

- Diet: Patients are started on liquids after their surgery then advanced to a general diet.

- Medicines: Your child may need any of the following:

- Antibiotics: To help prevent or treat an infection caused by bacteria.

- Anti-nausea medicine: To control vomiting (throwing up).

- Pain medicine: Pain medicine can include acetaminophen (Tylenol®), ibuprofen (Motrin®), or narcotics. These medicines can be given by vein or by mouth.

- Stool softeners: Polyethylene glycol (Miralax®), Docusate (Colace®) or senna are among the medications used to avoid straining after surgery.

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: Your child may eat a normal diet after surgery. Avoid constipating foods such as dairy products, rice and bananas.

- Activity: Your child should avoid strenuous activity and heavy lifting for the first 1-2 weeks after laparoscopic surgery, 4-6 weeks after open surgery.

- Wound care: Surgical incisions should be kept clean and dry for a few days after surgery. Most of the time, the stitches used in children are absorbable and do not require removal. Your surgeon will give you specific guidance regarding wound care, including when your child can shower or bathe.

- Medicines: Medicines for pain such as acetaminophen (Tylenol®l) or ibuprofen (Motrin® or Advil®) or something stronger like a narcotic may be needed to help with pain for a few days after surgery. Stool softeners and laxatives are needed to help regular stooling after surgery, especially if narcotics are still needed for pain.

- What to call the doctor for: Call your doctor for worsening belly pain, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, problems with urination, or if the wounds are red or draining fluid.

- Follow-up care: Your child should follow up with his or her surgeon 2-3 weeks after surgery to ensure proper post-operative healing.

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

- The long-term prognosis for children with rectal prolapse is good. More than 90 percent of children who experience rectal prolapse between nine months and three years of age will respond to medical treatment and will not require surgery.

- Children who develop rectal prolapse after the age of four are more likely to have underlying neurologic or muscular defects of the pelvis. These children are less likely to respond to medical treatments and should be seen early for surgical intervention.

References

- Holcomb, George W III, et al. Ashcraft’s Pediatric Surgery. New York. Elsevier, 2014. E-book.

Updated: 11/2016

Author: Romeo C. Ignacio, Jr., MD; J. Liebig, MD

Editors: Patricia Lange, MD; Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Ruptured Appendicitis

Condition: Ruptured (Perforated) Appendicitis

Overview (“What is it?”)

Definition: Inflammation/Infection of the appendix

- The appendix is a small extension of the intestine that is connected to the large intestine (colon). The appendix is usually located in the right lower side of the belly, and it is tubular in shape. Its length differs based on the age. The appendix has no known important function.

- Appendicitis is inflammation and infection of the appendix and often results from blockage of the appendix by stool (feces). Sometimes the feces forms a small stone called a fecalith. Other causes of appendicitis include swelling of lymph tissues within the appendix wall because of recent infection; sometimes worms can also block the appendix.

- Once blockage of the appendix occurs, several things happen:

- The appendix cannot empty the mucus and fluid that it makes.

- The pressure in the appendix increases and it swells.

- Bacteria multiples inside the appendix.

- The swelling cuts off the blood supply to the appendix. If the infection continues, part of the appendix wall dies and a hole results. This is how ruptured or perforated appendix happens.

- Ruptured Appendicitis: The time interval between onset of symptoms and rupture of the appendix is about 36 to 72 hours. Rupture occurs in about one of three patients admitted to children’s hospitals. The severity of ruptured appendicitis is different for every patient. Some children have a small rupture, while others may have a big spillage of stool and pus into the abdomen. Still others can have problems with intestinal blockage from the inflammation and infection. Some children who have appendicitis going on for days before the diagnosis may be so sick that the infection spreads into the blood stream. This is a serious condition and can be life-threatening. These patients will need to be stabilized before undergoing surgery. Therefore, the treatment including timing of surgery depends on how sick the patient is.

- Incidence: There are 70,000 appendicitis cases in kids per year in the United States. Overall, 7% of people in the United States have their appendix removed during their lifetime.

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- Early signs:

- When inflammation in the appendix begins, there is pain around the middle of the belly by the belly button. The child may have decreased appetite and feels like vomiting. The pain never completely goes away and becomes sharper with time.

- Most children with appendicitis have a fever of 38°C to 39° C (100.5°F to 102°F).

- Later signs/symptoms: More than 24 hours after the pain starts, it moves to the right lower side of the belly. Sometimes, a child complains of right lower abdominal pain while walking or refuses to stand up or walk due to pain. Younger children (less than five years old) have a higher chance of having ruptured appendicitis because they may not be able to talk clearly about their symptoms. If the appendix ruptures, a high fever may be seen. There may be episodes of diarrhea.

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to find out what my child has?”)

- History: The doctor will obtain a history and perform a physical exam. This is important for diagnosis of appendicitis. The surgeon will be interested in the type and location of pain: right lower side that hurts with jumping, walking or other jarring movements. The doctor will ask whether the child may have nausea, vomiting, refusal to eat, fever or diarrhea.

- Physical examination: Includes a careful abdominal examination performed by the surgeon. Other medical problems that cause belly pain will be investigated.

- Laboratory tests: Bloodwork may be sent to look at suggestion of an infection. Urine may be tested for a bladder infection or a kidney stone. Female teenagers should have a urine pregnancy test.

- Diagnostic studies: In some cases, the child’s story and the examination by the doctor may be very convincing that appendicitis is present. If the diagnosis is not clear, other tests may be ordered:

- Chest X-ray: If there is a concern for pneumonia

- Abdominal X-ray: A belly X-ray looks for clues regarding what may be causing the pain in general.

- Ultrasound: Ultrasound is very helpful to diagnose appendicitis. A probe is placed over the belly and sound waves are used to look at the appendix. Ultrasound may be useful for girls to look at the ovaries.

- Computed tomographic (CT) scan: CT is most useful when the diagnosis is not clear or if ruptured appendicitis suspected. Unlike ultrasound, CT scan uses radiation to obtain images. The child may be asked to drink a liquid that outlines the stomach and intestines. Sometimes, the contrast is given through the rectum. In some cases, an IV medicine is needed to help the CT get better pictures leading to a more accurate diagnosis.

- Conditions that mimic appendicitis: Gastroenteritis (“stomach flu”), constipation, ovarian cyst, twisting of ovary (torsion), groin (inguinal) hernia, pneumonia, Meckel’s diverticulum, inflammatory bowel disease, kidney diseases, urinary tract infection, intestinal obstruction, pregnancy.

- It is important to note that

- Children with history and physical exam findings that are convincing with appendicitis may not need any further tests

- In children with unclear cause of belly pain, there are several possibilities.

- If the diagnosis of appendicitis is not clear, the doctor may recommend observation in the emergency room or hospital for a period of time. A doctor will examine the child every few hours to see if the pain gets better or worse.

- Ultrasound or CT may be done depending on the situation.

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child better?”)

- Medical treatment

- Since appendicitis is an infection, antibiotics are an important part of the treatment. Antibiotics are medicines that fight bacteria. It is given through the vein.

- Patients with ruptured appendicitis have a high risk of getting infection of their wound or developing an abscess or pus collection inside their belly. They need several days of antibiotics depending on how bad the rupture is.

- Fluids are needed for patients with appendicitis. Since appendicitis causes loss of appetite, the patient may be dehydrated. Fluids are usually given through the vein.

- Medicine is also given to the patient to help make their belly pain better.

- Since appendicitis is an infection, antibiotics are an important part of the treatment. Antibiotics are medicines that fight bacteria. It is given through the vein.

- Surgery: The standard way to treat appendicitis is by removing it (appendectomy). This can be done the traditional way (“open” or larger incision) or laparoscopic.

- Open appendectomy: The appendix is removed through a transverse open incision in the right lower part of the belly.

- Laparoscopic appendectomy: In laparoscopic appendectomy, several small cuts (incisions) are made. Through one of the cuts, a video camera is placed. The surgery itself is done using small instruments placed through the other incisions. The usual number of incisions (cuts) for laparoscopic surgery vary from one (single port umbilical) to three. Sometimes an extra cut is needed if the appendix is really ruptured and stuck. The placement of the incisions depends on the location of the appendix.

- Open and laparoscopic appendectomy take the same amount of time to perform. Appendectomies for ruptured appendicitis take longer than those for non-ruptured appendicitis. One benefit of laparoscopy is that other abdominal structures can be examined using the video camera during surgery. Laparoscopy also has lower risks of wound infection.

- Special circumstances with ruptured appendicitis and their treatment

- Ruptured appendicitis with abscess. Patients with ruptured appendicitis spill stool from the appendix into the belly. This causes an infection resulting in a collection of pus or an abscess. The abscess may be seen on ultrasound or CT. If the abscess is big, the surgeon may decide that the infected fluid should be drained first to calm down the infection before doing surgery. With an operation done when there is a large abscess, there is a higher complication rate than an operation done when the abscess is resolved.

- Drainage of the abscess is usually done by a specialist that will use either an ultrasound or CT to look for a safe window to drain the pus. Sometimes the window is through the front of the belly, the side of the belly or even through the opening of the anus. Placement of the drain depends where the abscess is located and the internal organs around it. Usually, the radiologist leaves a small drainage tube to allow all the infected fluid to come out. The drain is removed when all the pus has been drained.

- Drainage of the abscess and antibiotics settle the infection. The patient feels better and is able to be sent home. The appendix is removed weeks later.

- Ruptured appendicitis and intestinal obstruction:

- Sometimes the inflammation from ruptured appendicitis is so bad that it causes kinking of the intestines. This leads to blockage of the flow of food through the intestinal tract. Intestinal blockage or obstruction is suspected if the patient has lots of vomiting and the vomit is green or bright yellow in color. X-rays or CT may show intestinal obstruction.

- When obstruction is present, it usually means the appendicitis is severe. Although a laparoscopic approach may be possible, an open operation may be needed. This may require a large vertical incision in the middle of the belly.

- Preparation for surgery: Your child will be given fluids, antibiotics, pain medicine prior to surgery.

- Postoperative care

- Activity: Your child’s caregiver will tell you when it is okay for your child to get out of bed. Usually, the child is encouraged to walk around as soon as possible.

- Diet: In patients with ruptured appendicitis, it may take a few days for the intestines to work normally. Your doctor will make the decision when your child should ready to eat. This depends on many things such as how badly ruptured the appendix was, whether there was intestinal blockage, if your child is still vomiting, and whether he or she is passing gas.

- Foley catheter: Sometimes there is a tube or catheter that may be put into your child’s bladder to drain urine.

- Nasogastric tube: Sometimes a nasogastric (NG) tube is inserted through your child’s nose or mouth and down into his stomach. This tube keeps the stomach empty to decrease vomiting after surgery.

- Medicines: Your child may need any of the following:

- Antibiotics: This medicine is given to help prevent or treat an infection caused by bacteria.

- Anti-nausea medicine: This medicine may be given to control vomiting (throwing up).

- Pain medicine: Pain medicine can include acetaminophen (Tylenol®), ibuprofen (Motrin®), or narcotics. These medicines can be given by vein if the intestines are not fully working yet.

- Ruptured appendicitis with abscess. Patients with ruptured appendicitis spill stool from the appendix into the belly. This causes an infection resulting in a collection of pus or an abscess. The abscess may be seen on ultrasound or CT. If the abscess is big, the surgeon may decide that the infected fluid should be drained first to calm down the infection before doing surgery. With an operation done when there is a large abscess, there is a higher complication rate than an operation done when the abscess is resolved.

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: Your child may eat a normal diet after surgery.

- Activity: Your child should avoid strenuous activity and heavy lifting for the first 1-2 weeks after laparoscopic surgery, 4-6 weeks after open surgery.

- Wound care: Surgical incisions should be kept clean and dry for a few days after surgery. Most of the time, the stitches used in children are absorbable and do not require removal. Your surgeon will give you specific guidance regarding wound care, including when your child can shower or bathe.

- Medicines: Medicines for pain such as acetaminophen (Tylenol®) or ibuprofen (Motrin® or Advil®) or something stronger like a narcotic may be needed to help with pain for a few days after surgery. Stool softeners and laxatives are needed to help regular stooling after surgery, especially if narcotics are still needed for pain.

- What to call the doctor for: Call your doctor for worsening belly pain, fever 38.5°C (101oF), vomiting, jaundice, f the wounds are red or draining fluid, diarrhea or problems with urinating.

- Follow-up care: Your child should follow up with his or her surgeon 2-3 weeks after surgery to ensure proper post-operative healing.

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

- Patients do well after removal of appendix.

- Complications:

- Wound infection: Happens around 3% of the time. Infections may need only antibiotics or may require opening up of the wound depending on how bad the infection is.

- Abscesses (pus pockets): Happens about 10-20% of the time with ruptured appendicitis. If the abscess is small, antibiotics may treat it. If it is big, it may need to be drained. The technique is the same as described in the section Ruptured Appendicitis with Abscess

- Small bowel obstruction: 3-5% risk after appendicitis and appendectomy.

- Complications:

Updated: 11/2016

Author: Joanne E. Baerg, MD

Editors: Patricia Lange, MD; Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Sacrococcygeal Teratoma

Condition: Sacrococcygeal Teratoma

Overview (“What is it?”)

- Definition

- Sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) is a type of tumor that starts at the end of the tailbone (coccyx). It can be quite large and extend outside of the body and/or inside the belly. The tumor contains many different types of tissue including hair, teeth, bone, muscle, nerve, among others. There can be cancer tissue within SCT. The likelihood of cancer is higher in older children, and much less in newborns.

- Most SCT in newborns are non-cancerous.

- Epidemiology: SCTs are the most common tumor seen in newborn infants, occurring in 1 in 30,000-70,000 live births. SCTs are more common in girls. Most SCTs are found in infants, but some can be seen in toddlers and children four years or younger. Larger tumors, especially those outside the body, are often seen on prenatal ultrasound. Twelve to fifteen percent of children with SCTs have associated congenital anomalies, most commonly anorectal malformations and spinal abnormalities.

Signs and Symptoms (“What symptoms will my child have?”)

- Early signs

- Mass seen starting from tailbone

- In some cases, the tumor may be mostly within the belly and is difficult to diagnose on the outside.

- Tumor complications

- If the mass is very large, the heart has to pump large amounts of blood to the tumor. Symptoms of heart failure can be seen even while the baby is still in the uterus—such as fluid around the lungs, in the belly, around the heart and within the baby’s tissues. This condition is called “hydrops fetalis”.

- Bleeding from mass

- Tumor rupture: When the skin from the tumor rips off

- If a large part of tumor is inside the belly, it can block the flow of urine or stool.

Diagnosis (“What tests are done to find out what my child has?”)

- Labs and tests

- Blood tests: AFP, beta-HCG levels. These proteins are made by the tumor. Other blood tests such as blood count and electrolytes (minerals) will also be checked.

- Computed tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the abdomen/pelvis will look at how big the mass is, the extent of the tumor located and blood supply.

- Chest X-ray or CT to look for pulmonary spread.

- Conditions that mimic this condition

- Lipomeningocele, lipoma, chordoma (spinal cord anomalies)

- Rectal duplication

- Epidermoid cyst

- Neuroblastoma (tumor from neural crest cells)

Treatment (“What will be done to make my child better?”)

- Prenatal Care

- Since SCTs can have complications, the mother of the baby undergoes frequent visits to her obstetrician for check-ups and ultrasounds to monitor for signs of heart failure and/or hydrops

- In most cases of SCT that is external to the baby, a Caesarian section (C-section) is recommended to avoid bleeding or rupture of the tumor.

- Medicine

- There is no medicine to treat the mass, only surgery

- Surgery

- Preoperative preparation

- Studies as above

- Intravenous antibiotics to help prevent infection

- Procedure: The goal of the surgery is to completely remove the mass. Depending on the location, the cuts (incisions) needed for the surgery can be by the buttocks only (external masses), the belly only (internal masses) or both. The tailbone (coccyx) is removed with the tumor. Not removing the coccyx is associated with up to 40% recurrence of the tumor. Sometimes a small plastic drain is placed under the skin flaps of the buttock incision.

- The mass will be sent for examination to see if there are components of cancer in the mass.

- Postoperative care

- Baby often has to lay on belly for first couple of days after surgery to allow incision to heal

- Incisions may open up and need dressing changes

- Drain are usually left in place for 3-7 days after surgery

- Medications needed will include pain medications, antibiotics and maybe nutrition delivered through the vein

- If cancer is seen in the mass, the baby will need medicine (chemotherapy) to help control the recurrence of cancer. If this is the case, cancer specialists (oncologists) will be involved in the care of your baby.

- Preoperative preparation

- Risks

- Bleeding requiring transfusion

- Wound breakdown—the skin close to the tumor can have a fragile blood supply

- Wound infection

- Urinary retention—there is a high risk of urinary problems after this procedure, likely due to the stretch of the nerves and muscles of the pelvis. The length of time that this is a problem varies from one child to another.

- Incontinence of muscles of anus—there is a risk of having problem with continence of stool. Often the tumor stretches the muscles involved in control of continence. This will gradually get better in most cases.

- Benefits: Removal of mass

Home Care (“What do I need to do once my child goes home?”)

- Diet: Normal for age

- Activity: Normal for age

- Wound care: Depends on wound. May need to do dressing changes if wound had opened up. In this case, your surgeon will help explain wound management, as it differs from one child to another.

- Medicines: Pain medications such as acetaminophen (Tylenol®) may be needed.

- What to call the doctor for: Redness, warmth, or drainage from incision. Problems with urinating or stooling

- Follow-up care

- Regular follow-up with surgeon for physical examinations and checking AFP levels. Since AFP is made by the tumor, blood levels should normalize once the tumor is removed. AFP levels is followed regularly because if it increases, it signals tumor recurrence.

- If cancer is present in the mass or if there are metastases (tumor spread beyond the main tumor such as the lungs, for example), the child will need follow-up with oncology for chemotherapy

Long-Term Outcomes (“Are there future conditions to worry about?”)

Survival rate for sacrococcygeal teratomas is more than 95%. The risk of bowel or bladder dysfunction even in benign tumors is quoted as 30-40%. Tumor recurrence can happen, therefore careful follow up is needed.

Updated: 11/2016

Author: Grace Mak, MD

Editors: Patricia Lange, MD; Marjorie J. Arca, MD

Short Bowel Syndrome

Condition: Short Bowel Syndrome (also known as short gut syndrome, short gut, small intestinal insufficiency)

Overview (“What is it?”)

- Definition: Short Bowel Syndrome (SBS) is a condition in which the intestines, specifically the small intestine, are unable to digest and absorb the proper amount of nutrients from food to sustain life.